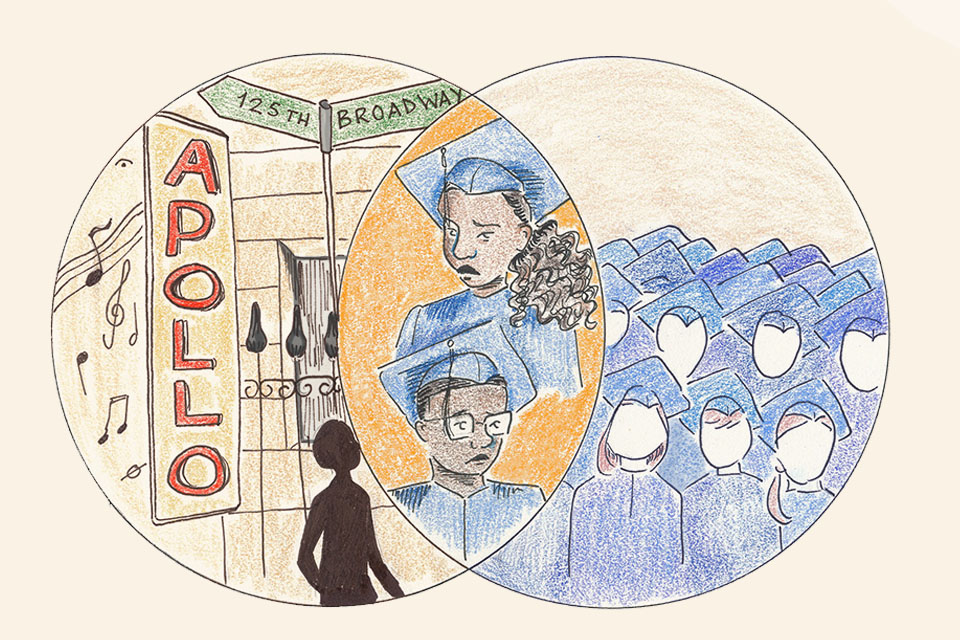

Take the A, B, C, or D train to the subway station at 125th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue. At the turnstiles, six tall images will introduce your entrance into the world above. The pictures depict a Harlem, but not the one into which you will soon enter upstairs. The black-and-white impression of a horse-drawn carriage plastered on a subway wall poses an odd and significant contrast to the Harlem that bustles above and around you.

The history of Harlem is just as long as it is diverse. Before thinking about how Columbia should preserve the historic character of Harlem, it is worth parsing out what its history and character actually are. Is Harlem those snapshots on the station wall, or the city and subway that move above and below them? Or is it something else entirely?

I arrive in Central Harlem on a bicycle, which I lock up on Lenox Avenue between the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and Harlem Hospital Center. It’s easy to find the walking tour group with whom I’ll be spending the next two hours. Harlem’s gentrification hasn’t yet reached this part of town, it seems. The streetscape is a mix of coloreds, so the small crowd of light-skinned folks loitering by a bike rack is conspicuous on the heavily trafficked street littered with the thrown-out flyers for Bob Avakian’s new book event at the library.

“Welcome to historic Harlem,” the guide says, and our tour begins.

Jared Orellana

Jared Orellana

Imagining Nieuw Haarlem

All communities have a founding myth, and one of Harlem’s begins with Dr. Johannes Mousnier de la Montagne.

In 1636, de la Montagne, a Huguenot fleeing Catholic France, arrived in the Dutch village of Capsee—present-day Battery Park. He came with his wife, his son Johannes Jr. (who liked horseback riding), and their newborn daughter Marie.

It was from there, within the imaginings of Manhattan’s first physician, residing on the southern tip of the island, that “Harlem” was born. Shortly after arriving in America, de la Montagne and his family, equipped with only a wooden dugout canoe and a paddle, made their way up the East River.

His trip is described in mythical beauty by Carl Horton Pierce in his 1903 book New Harlem Past and Present: The Story of an Amazing Civic Wrong, Now at Last to be Righted.

“This dauntless medical student took the paddle in his own uncalloused hands—a modern Ulysses, steering his way through strange and hazardous channels. … The lonely heron’s shrill cry alone broke the ‘sabbath stillness of the wilderness,’ and it may be supposed that as the Montagnes reached the end of Blackwell’s Island, and heard the roaring ‘as of a bull’ of Hellgate, their hearts were touched by some emotion of dread,” Pierce wrote.

De la Montagne and his family landed on the shore of the Harlem River at 105th Street. Following an American-Indian trail on Lenape hunting grounds, now St. Nicholas Avenue, de la Montagne made his way to where it now intersects with Seventh Avenue. Here, he constructed a wooden cabin for himself and his family.

By the time winter arrived, there were three settled households in Harlem. In March 1658, by the ordinance of New Netherland Director-General Peter Stuyvesant, the village of New Harlem, or Nieuw Haarlem, named for a small Dutch town, was officially established.

Families migrated uptown, paddling the three hours’ commute from New Amsterdam to New Harlem. When they arrived, they surveyed the land and staked plots in a stockaded village that, by 1664, had a church, a militia, and 23 families. It is said that back in those days, the area was so forested that one could shoot a deer for dinner from their kitchen door.

These Harlemites were farmers. Harlem women, dressed in short gowns and slippers, stayed inside spinning wool and flax to make clothes and bedsheets for themselves, their husbands, and their children.

On winter Sundays, the congregation would all sit in the pews with foot stoves to keep warm as they studied their silver-clasped Dutch bibles.

After doing business, Harlemites would gather for drinks at the Indian Trail Inn, chatting in Dutch about crops and horses and cattle.

This was their Harlem, but as a new addition to Columbia’s own landscape reminds us, it was by no means the first one.

Preserving amid a history of displacement

“Your time is coming, you white motherfuckers,” a black Harlemite spits out at the un-coloreds in my tour group as we pass 135th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard. About an hour later, underneath the ugly overhang of the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building, another black Harlemite feels that it’s his turn to make a guest appearance, overpowering the speech of our guide.

The old-timer, who unlike me is well dressed for the fall, soliloquises under the State Office Building: “Black spirit is here. All this gentrification stuff is gonna backfire. This is the beginning of the end,” he says ominously.

But displacement has been the recurring chorus in the song of Harlem’s history.

The beginning of the beginning of the end in Harlem actually reaches all the way back to the mid-17th century, when that one Huguenot landed off of the East River with his family. The idea of Harlem has its origins in the de la Montagnes’ bold trip, but the reality is that a neighborhood in the neck of Harlem’s woods had already been established by the Lenape Amerindian tribe.

Dressed in deerskins and smoking red copper tobacco pipes just south of current day Mount Morris Park Historic District, an area where bulrushes grew, the Lenape lived in longhouses furnished with mats and hatches and wooden dishes and more stone pipes for tobacco.

It is through the Dutch descriptions of the native people at this time that evidence of the first antagonistic reappropriation of Harlem emerges.

“The Indians are indolent, and some, crafty and wicked … but hospitable when well treated, ready to serve the white man for little compensation,” Dutch geographer Joannes de Laet wrote in 1625.

Over 250 years after the Dutch drove the Lenape from their land, the white people who lived in Harlem in the late 18th and early 19th century saw the migration of blacks, who were running away from racial violence and poor housing conditions, up to Harlem as just as much of a threat to their neighborhood as Columbia and other gentrifying agents are seen today.

“The Negro invasion … must be vigilantly fought,” reads a July 1911 edition of the now out-of-print Harlem Home News. “The invaders will slowly but surely drive the whites out of Harlem. We now warn owners of property. … The negro must have some place to live, but why must he always drive the white man out of his home in order to find a home for himself?”

It is likely that no homes now survive from this early era of Harlem. Michael Henry Adams, an historian and a founder of the preservation advocacy organization Save Harlem Now, writes in his book Harlem: Lost and Found that “the architecture of the first inhabitants of Harlem left almost no trace; even shortly after these [Native American] hunters and gatherers moved on, there would have been little sign of their early shelters.” And today, it seems that the most Dutch thing about Harlem is Amsterdam Avenue.

Considering this deficit in the history of Harlem, Columbia, as a piece of Harlem’s history itself, must, in all of its elements, continue to dedicate itself to the historical preservation of the many characters of this neighborhood.

Spaces to preserve

The daunting drizzle has come out of its clouds. Our guide smartly directs us to take shelter beneath the scaffolding surrounding the demolishment of what was once the Renaissance Casino and Ballroom.

It is clear that Bontemps’ Negrodom is now threatened. The sense of the loss, or death, of a neighbourhood is a reality for today’s Harlemites, and even for the tourists who can only imagine the long-gone glamour of landmarks left unpreserved.

The preservation movement in Harlem has largely been a losing battle. Carolyn Johnson, whose mother worked at Columbia for 35 years, is the owner and founder of Welcome To Harlem, a Harlem history tour company. She admits that finding parts of old Harlem on her tours is “like a scavenger hunt.” Moreover, what is preserved are those elements that are valuable in the eyes of the newcomers and not necessarily those meaningful and important to long-term residents.

The “Harlem” page on Wikipedia, whose collaborative platform makes it a more accurate reflection of people’s opinions than more restrictive organizations like the National Park Service and New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, lists at least 56 places in Harlem (not necessarily including Morningside Heights) that it considers to be historically prominent. These include the Abyssinian Baptist Church, the Harlem YMCA, and El Museo del Barrio.

Few would deny that these places are significant to Harlem. But what is even more significant to 23-year-old Hugo Torres-Fetsco, who has lived in the same apartment on Tiemann Place and Riverside Drive since the age of two, is the playground nicknamed “Dolphin Park” where he used to play as a child.

To Rodanne Smith, who’s been a resident of the Grant Houses located between 123rd and 125th streets for 50 years, it’s the supermarkets, the florists, the cleaners, the free student lunches and children’s summer camps and church programs.

Jared Orellana

Jared Orellana

For Maritta Dunn, who grew up in Harlem in the 1930s and ’40s, much of her Harlem is already gone: Prelude Club, Broadway Bar, a couple of Chinese restaurants—all have been swept away by the familiar tides of gentrification.

The 197-a plan, the proposal for neighborhood development by Manhattan Community Board 9 (the local government body whose jurisdiction includes Morningside Heights, Manhattanville, and Hamilton Heights), suggests 31 sites for study toward designation as historic landmarks in the district. Seven of these sites—Meeting with God Church on 130th Street, the Nash Building at 3280 Broadway, the Studebaker Building on 131st Street, Lee Brothers’ storage building on Riverside Drive, West Market Diner on 131st Street, and Skyline Windows on 130th Street—are owned by Columbia. Teachers College’s Bancroft Hall is one of 15 places proposed for designation as historic landmarks. Morningside Heights is one of five areas CB9 proposed for study toward historic district designation.

John Reddick, an architect, former member of the West Harlem Local Development Corporation’s board of directors, former co-chair of CB9’s Landmarks Preservation and Parks Committee, and a Columbia community scholar, says that “people come with a kind of mythic sense of [Harlem],” and certainly in writing about this neighborhood, myths have become a motif, most significantly the myth of a single, unified Harlem. Also, there is the myth of a single, unified Columbia as varying parts of the University work both towards and against the preservation of the neighborhood’s historic character.

Columbia exists in an interesting spot within Harlem. Not only because its campuses and its community are often seen as discordant with the neighborhood that surrounds it, but because, as Columbia helps to shape Harlem’s future, it simultaneously works to remember its past.

Columbia preserving the bones

Jared Orellana

Jared Orellana

“It is dawn on 125th Street. Families are rising. The train booms overhead; trolley tracks run between the cobblestones and the early morning traffic. Workers hurry to their jobs at the local automobile factories, printers, and storage companies. The largest employer in the area is the Sheffield Farms dairy, whose proud billboard boasts the motto, ‘For the Rising Generation,’ and shows a healthy child enjoying a glass of milk. Horse-drawn wagons emerge from a nearby stable building to distribute bottles across upper Manhattan.”

This is the Manhattanville that Columbia is preserving, as described in the online iteration of a University exhibit about the neighborhood in 1929. The exhibit, which is currently displayed in the Nash Building, tells the story of Sheffield Farms, a bottled milk manufacturing facility whose remains are being replaced by our new campus.

Columbia’s preservation of Manhattanville is contractually binding, as a result of Columbia’s voluntary signing of the Declaration of Covenants and Restrictions. While CB9’s 197-a plan is only a suggestion, the contract Columbia signed sets guidelines for the University’s expansion and requires that Columbia preserve the historic character of the Manhattanville neighborhood. It obliges the University to maintain the architectural integrity of the Prentice, Nash, and Studebaker buildings and to create an interpretative multimedia exhibit to document the history of the Sheffield Farms milk producing complex that used to exist on the current campus.

Beyond Manhattanville, Columbia has been engaged in the architectural preservation of Harlem since 1985, and for the past 20 years, preservation of the historical heritage of Morningside Heights has been a part of University policy. The Capital Project Management and Planning department of Columbia Facilities has an Exteriors and Historic Preservation team, which dedicates itself primarily to Morningside Heights, fixing damage and providing facelift to historic buildings.

Since July 1, 2007, the University has mandated that only Columbia Facilities or its associates may work on Columbia buildings so that, as is written in the University’s statement on the issue, “the design, construction, maintenance and repair of university facilities [are] accomplished in a manner consistent with the university’s … historic preservation concerns.”

So far, Columbia has restored over 250 buildings.

Columbia has also agreed to reduce displacement of current Harlem residents. In documents like the Manhattanville Community Benefits Agreement and the 197-a plan, the preservation of people through low-income housing and job creation is distinguished from historic preservation. But preserving people is preserving history, argues community activist Tom DeMott, who graduated from Columbia College in 1980.

“If you’re talking about historic preservation, you have to be talking about seeing the value of the Harlem community,” DeMott says. “One very significant part of the Harlem community is the damn people who live here.”

But in a neighborhood whose strong sense of community is being dashed into a new wave of nebulousness as a result of present social change, retention of today’s Harlem residents may seem an uncomfortable anachronism. Like Harlem’s historic Apollo Theater—now bookended by a GameStop and a Red Lobster—the low-income residents that Columbia seeks to save risk becoming out of place in their own home. None of the Harlemites interviewed for this story, however, seemed fearful that, in spite of keeping their houses, they may lose their sense of home.

“There’s just somethin’ about [Harlem],” Johnson says. “As much as it might change, some things are going to remain the same, and even with all of those people that are moving in, some of them will try to preserve and keep as much of that [Harlem] as possible.”

Beyond administrative preservation

The reality of this university is that, beyond the work of the administration, there is a committed cast of characters—disjointed faculty members, staff, and students—who are each working in ways both large and small to recognize and preserve the neighbourhood we live in.

My tour guide’s name is Clay Eaton. He’s a seventh-year Graduate School of Arts and Sciences student in the department of East Asian languages and cultures. All of the tour guides at Big Onion Walking Tours, a New York City walking tour group started by a former Columbia American history Ph.D. student in 1991, are Columbians. I actually found out about Big Onion through a Facebook advertisement in February advertising a free historic walking tour hosted by Undergraduate Student Life on the Columbia class of 2019 Facebook page.

“Given Columbia’s location, it is helpful for students to learn about Harlem,” Chia-Ying Pan writes to me via Facebook. Pan is Undergraduate Student Life’s director of education, outreach, and international student support, and she paid for the March tour.

But Eaton and the others at Big Onion represent just one layer of how common Columbians are preserving the history of Harlem.

A December 22, 2008 post on the blog Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York called “Capturing Manhattanville” tells the story of Daniella Zalcman, a 2009 graduate of Columbia College and a former managing editor of The Eye.

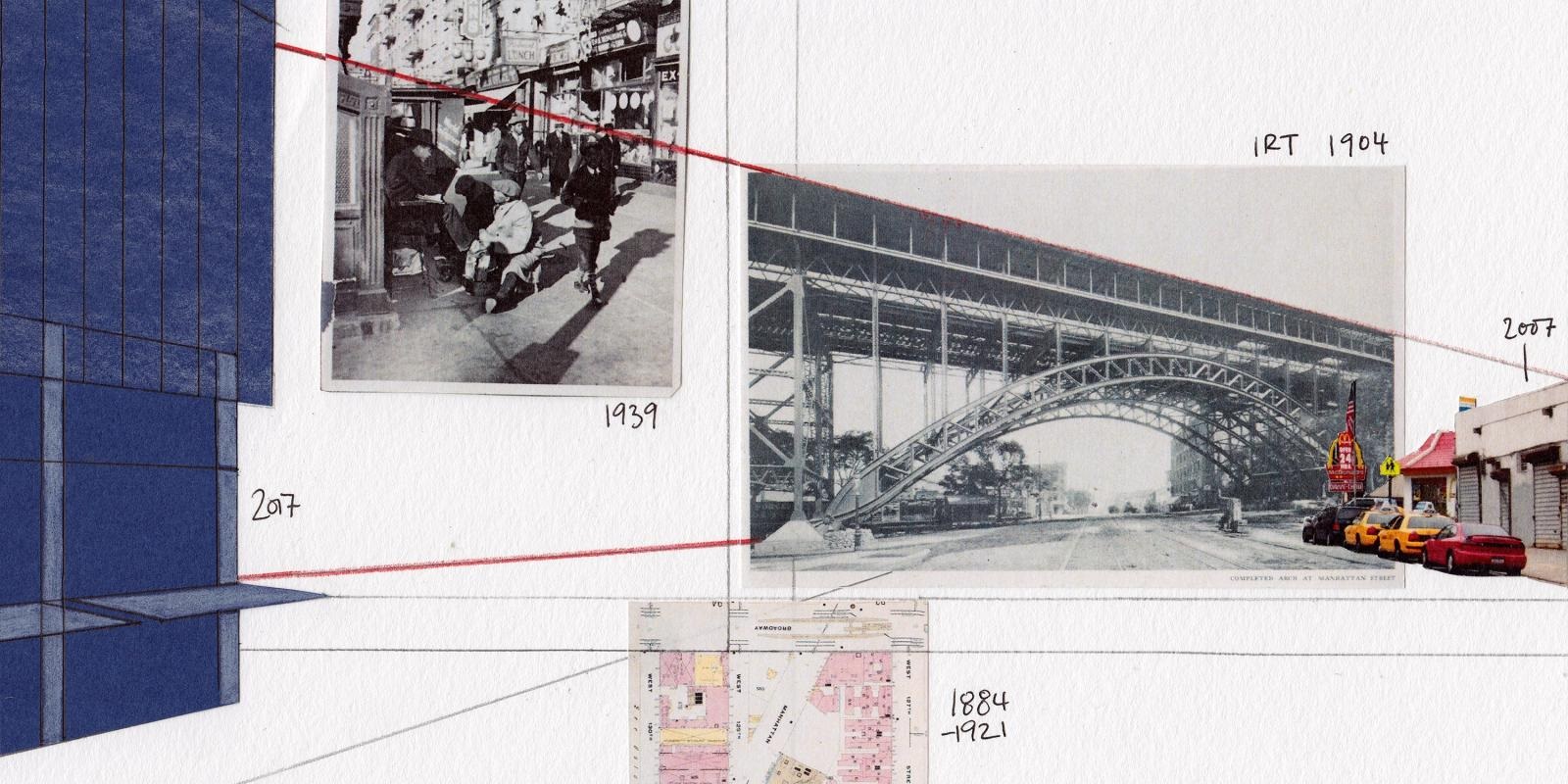

Zalcman, an architecture major, created for her senior thesis an encapsulation of time—a textual, pictorial, and videographic record remembering the history of Manhattanville and the state of the neighborhood as she witnessed it in the early phases of construction in 2009.

The Making of Manhattanville—what Zalcman named the website where she has displayed her work—“is an attempt to capture the neighborhood as it appears now,” as explained on the website’s “About” page. “Teetering on the cusp of that next great change.”

The capturing of Harlem and its neighborhoods is a task not only in the minds of Columbia students; it is an effort equally as present in the minds of many of their professors too. Harlem is one of the few New York neighborhoods specifically highlighted by Columbia history professor Kenneth Jackson in his popular course History of the City of New York. A professor at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Andrew Dolkart wrote the book Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture and Development. In 1953, the late John Atlee Kouwenhoven, who received a master’s degree at Columbia in 1933 and a Ph.D. in 1948 and was a Barnard English professor, published The Columbia Historical Portrait of New York; An Essay in Graphic History in Honor of the Tricentennial of New York City and the Bicentennial of Columbia University, which included a variety of historic images of Harlem.

In 2004, as a part of the Columbia 250 project—“a digital memory box of Columbia history” in honor of the University’s 250th anniversary—the contributions of Dolkart, Jackson (who was one of the co-chairs of the project’s steering committee), and others manifested in a section of the project called “Harlem History.”

As the director of the Lehman Center for American History, Jackson also contributes to some of the historical exhibitions at the Columbia libraries such as “Harlem Views: Perspectives from the Collections of Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library,” which ended on July 31.

Enter the word “Harlem” into the search bar of the Columbia University Directory of Classes, and 13 results appear.

Type it out again onto the Teachers College course schedule search, and there will pop up one more. On most Wednesdays from 5:10 to 6:50 p.m., assistant professor of history and education Ansley Erickson teaches a class called Harlem Stories, a two-semester course that focuses “on the history of education in Harlem.”

Erickson’s class is a supplement to a much larger project that she’s been working on for the past few years with professor of education Ernest Morrell called Educating Harlem, which their website describes as “a collaborative investigation into the history of education in 20th century Harlem.”

Morrell stresses that his and Erickson’s research is not only analytical but is inclusive of the Harlem community. “There’s all sorts of tools that Columbia has,” Morrell says. “We have people that can devote their entire lives to studying history, but the community itself is an asset. The model of history work that we are trying to engage in is one that engages with the community, not one in a community or about a community.”

Restricted access

Restrictions on certain aspects of Columbia, though, can make community access and engagement challenging, presenting an obstacle to the University’s ability to preserve Harlem’s history not only for Columbia, but for Harlem itself.

Located next to Blue Java Coffee Bar on the first floor of Butler Library, the Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning, an in-house group that creates classroom new media supplements, has at least 10 projects that either directly or tangentially relate to the history of Harlem. Of those 10, two are public access, three private access, and half are Columbia access only.

Maurice Matiz, the director of the CTL, believes that many of the private or Columbia access only projects could benefit the public.

The problem, he explains, is copyright. Much of what the CTL makes draws heavily upon material not owned by Columbia. For example, the Harlem Health History project, which was “created to enhance students’ historical research on health-focused social movements in an African American community,” includes “health reports and studies, news articles, advertisements, images, and interviews,” many of which Columbia did not receive permission to publish. To pay for permissions for each piece of material would be very costly, but reuse of material isn’t an issue when it is kept confined to the private classroom.

Regardless, lack of public accessibility and community engagement is one of the most prominent criticisms waged against Columbia’s attempts at preservation.

Many of the Columbians and all of the Harlemites interviewed for this story had never heard of Columbia’s Sheffield Farms exhibit. This even includes those like Walter South, former co-chair of the CB9 Landmarks Preservation and Parks Committee and the vice chair of the 197-a planning committee, who lives in the old headquarters of the Pure Milk League near Riverside Drive.

Currently, the exhibit is advertised through fliers handed out to different Columbia departments and at some schools near the Manhattanville campus, but Leonard Cox, the assistant vice president of strategic communications and the film producer for the exhibit’s senior project team, admits that, in spite of these efforts, there have been only about 100 visitors to the exhibit since its opening six months ago.

Even if someone is able to learn about and locate the exhibit, its position in a Columbia office building makes it feel inaccessible and unappealing to the community according to Reddick.

“Most people don’t have that comfort factor [to go to a Columbia building],” Reddick points out. “To say there’s an exhibit in the Nash Building and think in any way it has outreach. … Why don’t they put it somewhere where the community really goes all the time? … It’s like saying, ‘It’s hanging in the closet on the fifth floor of the Nash Building.’ Who gets there? It’s a joke.”

None of the preservation at the Manhattanville campus seems to extend beyond the University’s 17 acres. Our preservation of Manhattanville, it seems, is limited to the memorializing of Columbia’s Manhattanville.

Many community members criticize the University’s 197-c rezoning plan as preservation that focuses only on the bare minimum and that still sacrifices important historic value in the neighborhood for the sake of an architecturally out-of-context new campus.

The 197-a plan’s proposed historic preservation is far more extensive than that included in Columbia’s 197-c rezoning plan. A framework comparison between CB9’s 197-a plan and Columbia’s 197-c plan created by the Pratt Center for Community Development supports the assertion made in CB9’s review of the 197-c plan that “the neighborhood’s dynamic, richly layered historic, ethnic and cultural character, that would be preserved under the 197-a Plan, would be eliminated under Columbia’s 197-c proposal.” In other words, Columbia’s plan is more historically destructive than the community’s.

The 197-a plan recommends that, for contextual zoning of the neighborhood, the traditional street walls should be maintained. The 197-a plan “also preserves diverse architectural styles and historic character.” Columbia’s plan sets the street wall back along the majority of 12th Avenue, allows for taller buildings than the 197-a, “and requires the demolition of most of the properties considered by the 197-a Plan to be of historic value.”

Whereas CB9’s plan “identifies 14 buildings, Riverside Drive and IRT viaducts, and the Third Avenue Railway Turnaround on 12th Avenue between St. Clair Place and 125th Street for preservation through formal designation,” Columbia’s plan “does not seek formal designation and the resulting regulation of any historic properties.”

Prentis, Nash, and Studebaker are the only buildings of historic value on the Manhattanville campus that the University has preserved. In addition, it has saved the West Market Diner and the façade of the old Sheffield Farms Stable building, which it has moved to a location off campus, further uptown.

“How can only three or four buildings preserve the character of a neighborhood?” community scholar and neighborhood historian Eric K. Washington asks in a June 18, 2007 article in Architectural Record titled “Piano, SOM’s Columbia Plan Stirs Controversy.” “That’s a lot of responsibility for four buildings.”

Furthermore, the loss of the Sheffield Farms Stable, according to the Manhattanville campus’ Final Environmental Impact Statement—a predictive analysis of the expansion’s effects on the surrounding neighborhood—is a “significantly adverse” impact to the maintenance of the historic architectural context of the area.

Anne Whitman, the former owner of the stable building and the owner of Hudson Moving and Storage, was unable to speak on the record for this story due to a confidentiality agreement she signed with Columbia about the Sheffield Farms building.

However, an October 18, 2006 post on a blog called Eminent Domain Abuse hints at what may still be Whitman’s feelings about the Manhattanville project’s preservation efforts.

“They want to bulldoze my property after they steal it away from me for their private purposes through eminent domain abuse,” Whitman writes of Columbia and the historic stable building. “Their plan is anti-affirmative action and anti-historic preservation.”

Even in Morningside Heights, Columbia’s historic preservation of the neighborhood has been the cause of controversy—particularly a 2008 plan to demolish three historic brownstones on 115th Street.

One of the most popular arguments in support of keeping old buildings like the Sheffield Farms Stable building and the 115th Street brownstones is that they keep the old stories of an area.

“Old neighborhoods go through changes,” says Barnard urban studies assistant professor Aaron Passell, who studies the relationship between historic preservation and gentrification. “If we can find the structures that have formed the physical environment of that neighborhood, we can connect social moments to those structures, but if those structures are gone, we lose that opportunity.”

Completing our history

For the oldest of old neighborhoods in New York City, that opportunity seems to have already been lost. Out of the four books, one zine, and countless online articles used as research for this article, only one—Adams’ Harlem: Lost And Found—gives more than a cursory description of the Lenape: the people who lived in Harlem before it was hip, who lived in Harlem before it was Haarlem.

Perhaps this scarcity of a native historic narrative is only the result of the random happenstance of which books I brought out of Butler Library, but historic preservation can be a sad business. Many things can be constructed out of existence, beyond recognition and repair, and today, only 0.3 percent of Harlemites are Native American or Alaskan.

Columbia has had for a while a plaque dedicated to the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776, but it was only this year that plans were carried out to memorialize those people who have been here since before anyone had ever heard of New Harlem or New York or even the New World. The whitewashing and black-washing (most of the descriptions of Dutch Harlem also came primarily from only one of the books used in research for this article) of Harlem’s history certainly seems to be much more than an historical happenstance.

Two evenings ago, through the open cracks of the windows of my third floor Contemporary Civilization class in Hamilton Hall, I heard Harlem music. Not a saxophone or a zither—I heard a drum, beating to the chants of the Native American Council, huddled out in the crisp fall chill to dedicate a plaque of their own to this land.

It was only a few minutes before my professor asked someone to close the window. We had shut them out, metaphorically speaking, or so it seemed, but the new plaque here is a vital indication of the resilience of all of our Harlems.

Xavier Dade

Xavier Dade

The end of the tour

We finish a few minutes late. I am rushing back to Columbia in the rain, trying to make it to Dodge Fitness Center in time for my lifeguarding shift at 3. Once I’ve relaxed into the chair, the sight and sound of the steady swoosh of fingertips that glide across chlorinated water lulls me into recollections of a passage from a book I borrowed from Butler.

“From 1666 to 1668, the Hudson River formed the western boundary of the Harlem lands and properties. The same Hudson River flows between the same banks in 1903, although made up of different particles of water. The Town of New Harlem existed in 1666; and the same Town of New Harlem exists today, in 1903, although made up of different ‘particles,’ or members.”

On the tour, we saw a Popeyes, an IHOP, a parking lot, a hair salon. Later, I ask Eaton why he didn’t show us pictures of the ballrooms and headquarters and housing that once occupied the space of this now-nondescript city scenery. He has pictures, he says, and shows me that they are tucked with his notes inside the crook of his arm.

“It’s important to see the neighborhood now,” he tells me, “rather than as it existed.”

The sad reality, though, is that Harlem’s present transformation affects our vision of its past. When we reached one of the last stops on the tour, a street corner from which Eaton told us to direct our eyes at City College of New York’s Shepherd Hall, we had to step off into the street in front of a dumpster. The scaffolding at an adjacent construction site was obstructing our view.

__Daniela Casalino

__Daniela Casalino![]() THE EYE MAGAZINE OF THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

THE EYE MAGAZINE OF THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

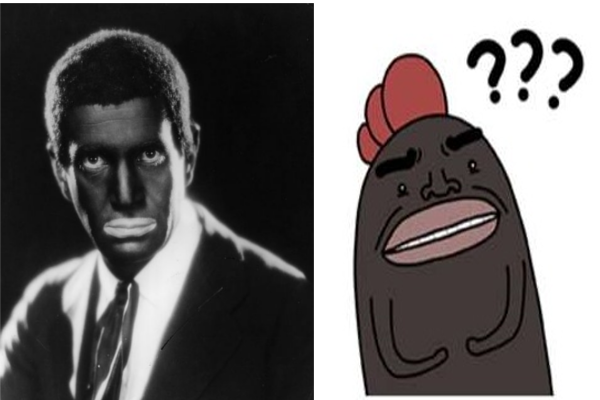

news.mydrivers.com

news.mydrivers.com Dailymail

Dailymail Tumblr, WeChat

Tumblr, WeChat “Fat, African Slob” (WeChat)

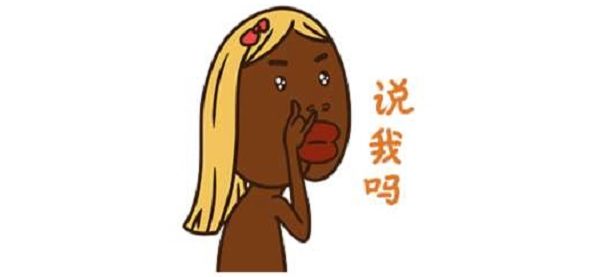

“Fat, African Slob” (WeChat) “Are you talking about me” (WeChat)

“Are you talking about me” (WeChat)

Non-Black and non-blackface stickers identified on WeChat as 黑人问号. (WeChat)

Non-Black and non-blackface stickers identified on WeChat as 黑人问号. (WeChat) A drawing of a pickaninny beside a 黑人问号 WeChat sticker. (historyonthenet.com, WeChat)

A drawing of a pickaninny beside a 黑人问号 WeChat sticker. (historyonthenet.com, WeChat) A visual play on words that both says Black person “黑人” and black dog “黑犬.” (WeChat)

A visual play on words that both says Black person “黑人” and black dog “黑犬.” (WeChat) “African Chief” (WeChat)

“African Chief” (WeChat) The sticker on the left reads “Africa”, on the right “Europe.” These are the only continents represented in this sticker gallery. (WeChat)

The sticker on the left reads “Africa”, on the right “Europe.” These are the only continents represented in this sticker gallery. (WeChat) Alexander McNab

Alexander McNab Alexander McNab

Alexander McNab Alexander McNab

Alexander McNab Alexander McNab

Alexander McNab Alexander McNab

Alexander McNab Maddie Morris

Maddie Morris

Amanda Frame

Amanda Frame Amanda Frame

Amanda Frame Jaime Danies

Jaime Danies Amanda Frame

Amanda Frame

Jared Orellana

Jared Orellana Jared Orellana

Jared Orellana Jared Orellana

Jared Orellana

Xavier Dade

Xavier Dade Courtesy of Tom DeMott

Courtesy of Tom DeMott Leon Wu

Leon Wu Charles Wenzelberg

Charles Wenzelberg Michael Norcia

Michael Norcia Thomas Guercio

Thomas Guercio Facebook

Facebook

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-tronc.s3.amazonaws.com/public/YKCSPGGI6VBBNNL6SBC4P3WT3Y.jpg) New York City Law Department

New York City Law Department Chester Higgins, Jr.

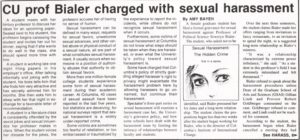

Chester Higgins, Jr. Columbia Daily Spectator/Nov. 19, 1986

Columbia Daily Spectator/Nov. 19, 1986 Steve Schapiro

Steve Schapiro Columbia Daily Spectator/Apr. 11, 2019

Columbia Daily Spectator/Apr. 11, 2019 New York Daily News/Apr. 21, 1989

New York Daily News/Apr. 21, 1989

Ian@NZFlickr

Ian@NZFlickr Kaila Jones

Kaila Jones Chris Humphrey

Chris Humphrey Chris Humphrey

Chris Humphrey