__Daniela Casalino

__Daniela Casalino

MARCH 28, 2017 | ![]() THE EYE MAGAZINE OF THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

THE EYE MAGAZINE OF THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

A black man walks into a barber shop in the basement of the building on the corner of 114th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, where Strokos is now. James Franklyn Bourne, who graduated from Columbia College in 1937, and his friend, also a student at Columbia, are there for the 35 cent haircuts that Ralph’s Barber Shop has been advertising in Spectator since the late 1920s. That was back when the owner, Ralph Robibero, was still at his old location, next to Casa Italiana on 117th Street and Amsterdam.

In 1936, Bourne and his friend wait for their turn at the barber’s chair. One of the store’s 10 barbers shouts out, “Next!” and the two Columbia men walk up, ready to redo their ‘dos. But then, something unexpected happens. The barber at this shop that is proud of its “first-class service” turns to Bourne and says, “You cannot be served here. Your color is too dark. It is against the policy of the barber shop.”

Bourne’s money was not welcomed. Meanwhile, Bourne’s friend, who was white, was served without a problem. This story is a sad reminder of the climate of racial discrimination that has plagued this country, this city, and this university throughout its existence. Unlike so many of these stories, however, this one ends somewhat happily.

Columbia students boycotted Robibero and other barbers across the neighborhood. The Negro Problems Committee of the American Student Union’s Columbia chapter rounded up over 50 students to act as pickets against the racist barber shops. At the urging of student activists, these barber shops agreed to an anti-discrimination pledge. That May, just before the end of the semester, Bourne received a personal invitation from Ernest Kopp, another barber, for a “first-class hair cut” at his own shop, also on Amsterdam Avenue.

However, the true significance of this story is not simply its moral of misplaced prejudice and the power of students to create meaningful change in their neighborhoods. Something more than white supremacy alone was at play. Less talked about and perhaps less obvious is the question of identity that lies at the deepest core of this story. What was sought by all actors in this social drama was more than just a reaffirmation of the place of black people in American society. Whether or not they were conscious of it, Bourne, Robibero, Kopp, and the Negro Problems Committee were really seeking the answer to the question of just who was James Franklyn Bourne.

In the eyes of some, he was a Columbian, just as Columbia-blue-blooded as Roar-ee the Lion or Alma Mater. He was the piano accompanist for the Glee Club, and he played Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie in the 1936 Varsity Show.

Perhaps others saw Bourne as only a black man, an identity that some saw as incompatible with Columbianness. But for Robibero, Bourne—Frank, as his friends called him—was likely neither of these things.

As an early response to student protests, Robibero promised to make a special exception to his store’s discrimination policy. In a letter to the editor published in Spectator, Robibero recalled, “I promised to serve only the Negro students of Columbia,”—as opposed to other black customers—“provided a list of their names were given to me.”

In this act of exceptionalism for black Columbia students, Robibero expressed that, for him, Bourne and his black classmates were neither fully black nor fully Columbian. A fully black person would simply not be served at the barber shop. Their name would not have appeared on Robibero’s list. A fully Columbian person’s name would not be on the list, either, but they would be served regardless. In 1936, a majority of Columbians were white. Black Columbians existed in a sort of a twilight zone, an uncomfortable in-between space of perpetual liminality that didn’t fit into contemporary social structures.

Today, 42 percent of students and 28 percent of faculty identify as minorities, but the lived paradox of being a student of color and a Columbian still exists for many.

There is “a battle within the African-American students between their Blackness and the perceived Whiteness of the university,” write the authors of the 2013 academic article “Understanding the African-American Student Experience in Higher Education Through a Relational Dialectics Perspective.” Such language may seem alarmist, but studies conducted by doctoral students and researchers at Sam Houston State University, Rutgers University and University of California at Berkeley, Seton Hall University, American University and University of the District of Columbia, and journalists at National Public Radio have all determined that the identity clash waged within these students can negatively impact their personal, professional, and academic development.

• • •

One solution for combating these developmental issues is to ensure that students of color are able to find a familiar cultural community within the gates of their heavily white campuses. The authors of the article “Self-Identity: A Key to Black Student Success” write that schools should “create an environment that is encouraging and embracing for Black students throughout the campus” and that “the opportunity to connect with others in the Black community helps to alleviate isolation.”

What these studies do not consider, however, is what happens in the case of Columbia, a seemingly white campus in a black community. Is Harlem an environment that encourages and embraces black Columbia students? Can Harlem alleviate black isolation? If it can, how do black students take advantage of Harlem? What functions do black environments on campus serve that Harlem cannot?

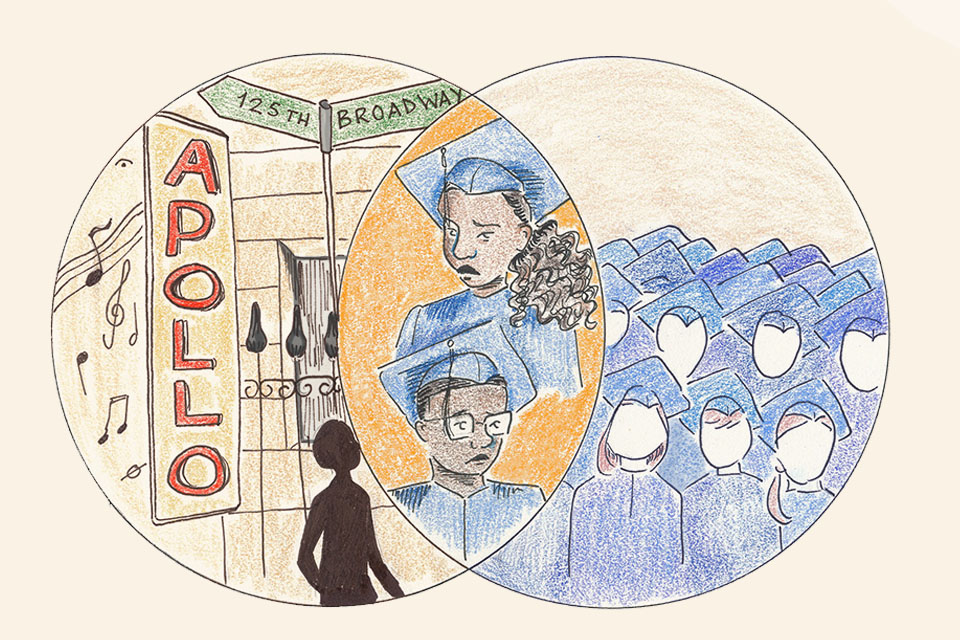

If the black student at a white university is an enigma, then understanding the black student experience at Columbia University seems almost impossible. We black Columbians move through our time here in a small, sloppily-sandwiched space between the blue lion of our white university and the dark faces of our black neighbors next door. In between the lion and the dark place, we search for cultural comfort and an area of our own, the overlap of the two opposing circles of the Venn diagram of our identities.

Last spring, I had my own strange experience on Amsterdam Avenue. On a chilly Saturday in January, I walked out of Apple Tree Supermarket. Just as I passed the store’s threshold and stepped onto the street, I was stopped by two employees, one of whom accused me of stealing. I was patted down. They didn’t find anything, because there was nothing to be found.

“You’re free,” I was told, and I left. Feeling that I had been wrongly racially profiled, “I walked back out onto the street and past Morningside Park into Harlem, where I could be around other black bodies for awhile.”

To me, my experience at Apple Tree was a challenge of my identity, just as Bourne’s barber shop experience 80 years earlier had been a questioning of his. Apple Tree is designated a Columbia University Safe Haven, but I did not feel safe in that space at that moment. I felt that negative connotations had been attached to the color of my skin, which was co-opted and used against me. The owner of the store responded, but only after I wrote an article about what happened to me. And regardless, I did not feel that I would be able to find the solace of racial solidarity within my school, and so immediately after my encounter at Apple Tree, I did not return to Columbia. Instead, I turned to Harlem.

In speaking with other students of color and Columbia alumni, veterans of this internal identity struggle, I have come to understand that my experience of a cultural homecoming in Harlem—which exists in spite of the fact that I originate from a place nearly 3,000 miles from here—is not unique among Columbians of color. Throughout time and across shades of darkness, Columbia’s neighborhood (usually north and east of campus) has become a community for some of us minority students who, while here on campus, are often confined to small spaces of color, cooped up into a lounge in Hartley Hall or the seventh floor of Brooks Hall like dysfunctional dolls on the Island of Misfit Toys.

Tom Kappner is a tall, light-skinned man, who lived in a variety of South American countries before coming to Columbia in 1962. He tells me that “there were seven of us,” referring to Latinos at Columbia at the time, and that “the diversity was in the neighborhood.”

During his freshman orientation, Kappner remembers being warned to not go down to “that” neighborhood.

“Even they told us not to go below 110th Street,” Kappner recalls. “That was a no-no because that was a mostly Latino neighborhood in those days.”

But as a Latino himself, it was precisely this cultural difference between the community and Columbia that attracted Kappner to the areas off campus. In Harlem, whose boundaries have shifted over time, Kappner felt that he belonged. With the diverse local community, Kappner could speak Spanish, his first language, con la gente en la calle.

“I left the campus as soon as I could,” says Kappner, who still lives within walking distance of Columbia. “I was much more at home in the community. That’s where I found people I could relate to… They were my people.”

Even so, there are and have been efforts to help Columbia students find their people on their campus. During the fall of Kappner’s junior year, the Student Afro-American Society was founded at Columbia as a space where “Caucasoids and Mongoloids are welcome, but it is toward the Negro, specifically the ‘Ivy League’ Negro, that the organization’s goals are aimed.”

Multiple people on the board of the Columbia University Black Students’ Organization (BSO) and the Barnard Organization of Soul Sisters, arguably the two largest and most influential spaces for the “Ivy League Negro” today at Columbia, were repeatedly contacted for this story, but neither group was able to comment in time for publication.

While the Student Afro-American Society, which was active in the 1960s, and the Black Students’ Organization, the Barnard Organization of Soul Sisters, and other similar groups undoubtedly were and still are sources of solidarity, community, and cultural affirmation on campus, they are not panaceas for the paradox of colored Columbians.

Kevin C. Matthews, who graduated from Columbia College in 1980, was a Negro in the Ivy League, but he did not necessarily feel like an “Ivy League Negro.”

“I wasn’t comfortable with the BSO,” Matthews admits. “When I came to Columbia and I went to my first BSO meeting or two, I thought they were a bunch of pretenders. I really did. I didn’t feel any connection to them.”

Coming from a rough, black area of South Jamaica, Queens, Matthews didn’t fit in with many of the prep school students in the BSO. In fact, he felt that many of the other black students looked down on him.

“I was a poor kid,” Matthews says. “I looked like a New York City thug, and the way [some of the other black students] looked at me and treated me, I was horrified, and I couldn’t smack ‘em in the face, so I just said, ‘Well, heck with it.’ So I just kinda stepped away.”

Many Columbians of color, past and present, have experienced the reverse of Matthews’ class-based alienation as they have interacted with the local neighborhood. Their Columbia identities—carried in their pretentious postures as well as in their pockets—keep many of them from la calle. Their Ivy League identity de-racializes them as ambiguous others in relation to the Harlem community.

In a 1967 letter to the editor, Ernest Holsendolph CC ’58, wrote that “young Negroes selected [to attend Columbia] in miniscule numbers in years past were more ‘white’ than Negro, which is probably why we were chosen.”

One black sophomore in 1972, writing under the pseudonym W.E.B. DuBois, even asserted that “being Ivy League, blacks on this campus feel isolated from the surrounding community,” a feeling entirely at odds with experiences like Kappner’s or like the 1967 Spectator article “Harlem: Puzzle for CU Negroes,” which asserts that “for an annually increasing number of Negro students, Harlem is home.”

I was unable to reach any local community members who would comment on the difficult-to-reconcile idea of black Columbia students, but the nature of these things is that they are much more often felt than spoken. Even without articulation, this feeling of whiteness in relation to Harlem can become just as immovable an obstacle to connecting with the community as Matthews’ class background was to connecting with other blue and white bruthas.

Just as the Malcolm X Lounge does not resemble Malcolm X Boulevard, so the black and brown people who occupy these places don’t always share in the same culture.

When Matthews stepped away from the black community at Columbia, he did not go into Harlem. He stepped instead back out into South Jamaica, Queens, an hour and a half each way, three times a week.

In his junior year, Matthews finally found his place at Columbia, but he did not connect through race. Matthews took a work-study job at the Columbia division of the Higher Education Opportunity Program, of which he was a part, and he became a peer counselor for other New York City native college students from low-income backgrounds. Ironically, it was Matthews’ economic background, which had segregated him from the community of Columbians of color, that led him to his eventual home in Morningside Heights. Maybe even more ironically, Matthews is now the president of the Columbia Black Alumni Council and lives in Harlem with his wife, a Latina Barnard alumna.

“Sometimes,” Matthews tells me from our seats in Strokos, just above where Bourne almost had his haircut, “we look to find people who look like ourselves to find strength, but it doesn’t mean that all black people only find strength from people that look like us. It’s an individual thing.”

In seeking the answers to these questions of community, I have overlooked its most essential part: the individuals.

The racial identity of each black Columbian is not only too complicated for Columbia and too hard to handle for Harlem, it also varies within the “black Columbia” community itself.

Perhaps we are a community without a culture. Some of us are from boarding schools. Some of us are from around the block. Some of us find refuge in our race. Some of us refuse to recognize it.

Perhaps it is in this way that we will be most able to connect to Harlem. Harlem, while black, is diverse. It is french fries and frijoles and fried chicken. It’s hip-hop and bachata and rock and roll. Harlem is the homeless man in front of the grocery store. It is the woman behind the counter of a coffee shop. It is the new family just now making the move uptown.

Harlem is diverse, and so are we, and so am I.