enemy of the state

The Alum Behind the Activism

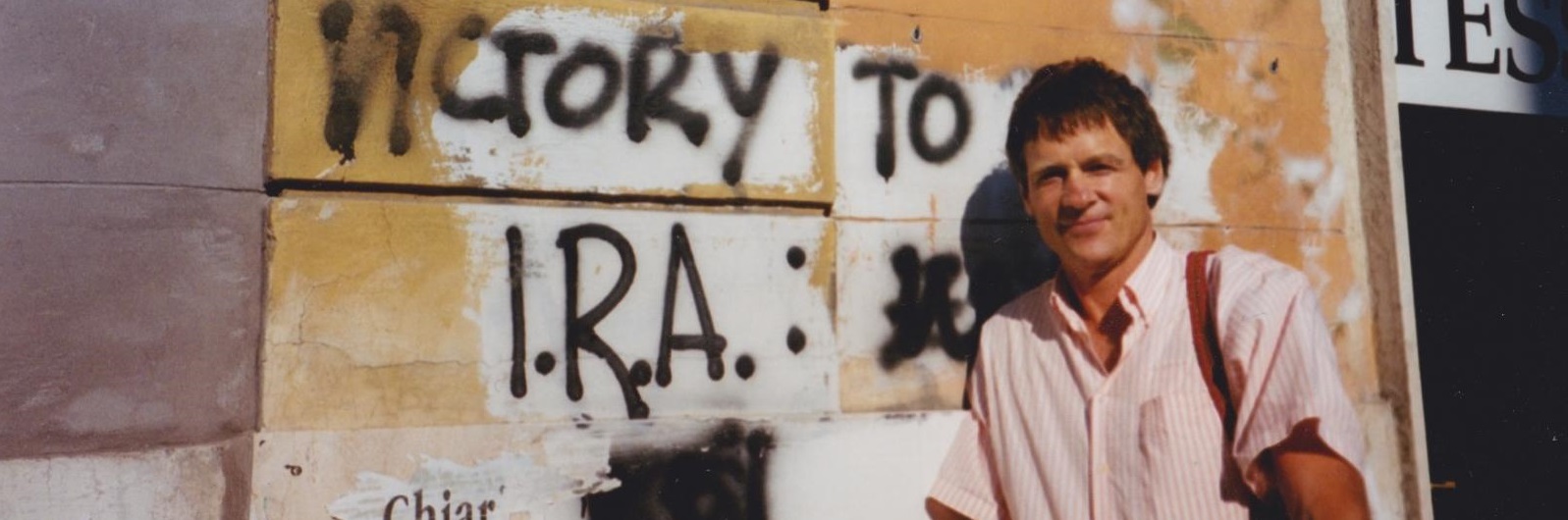

Courtesy of Tom DeMott

Courtesy of Tom DeMott

OCTOBER 26, 2016| ![]() THE EYE MAGAZINE OF THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

THE EYE MAGAZINE OF THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

“HARLEM!” shouts Tom DeMott, a graduate of Columbia College, class of 1980. “Is not for sale!” replies a small crowd, clapping along to the beat of a snare drum.

Beneath the crook of his right arm, DeMott holds a turquoise-colored sign. “FUERA COLUMBIA,” (Spanish for “Get Out Columbia”) is written on it in bold, black Sharpie above the words “HARLEM IS NOT FOR SALE.”

It’s March 8th, 2011, but DeMott’s been protesting since 1969. He’s demonstrated against a myriad of University issues, including Columbia’s involvement in the Vietnam War and its plans to build a gym in Morningside Park with a separate entrance and lower quality facilities for local community members. Marching around the entrance of the 125th Street 1 train station on this chilly Tuesday, DeMott is protesting the University’s Manhattanville campus expansion plan, leading an anti-Columbia movement that has caused WikiCU to dub DeMott “an enemy of the state.”

Five years later, I find this enemy of the state sitting on a piano bench in his apartment. His long, gray hair stops just above his blue and white checkered shirt. It’s unbuttoned halfway, making the New York city slicker look like a surfer boy, palms resting on his blue jeans and a beaded bracelet decorating his deeply tanned right wrist.

“Hi poopy doopy! How ya doin’?” DeMott asks his four-year-old granddaughter Shailaya as she runs into the room. He moves and leans back against the white cushions of the couch that faces the window; a cat relaxes in a rocking chair nearby. Shailaya snuggles up into DeMott’s denim lap.

“Help me Jesus to know where I’m goin’,” he sings softly to Shailaya over the strums of his guitar. The living room is aglow with notes and melodies and the low light of a late Thursday afternoon shining through the windowpanes on the quiet corner of Riverside Drive and Tiemann Place.

DeMott’s been at home in NYC since 1969; his house borders the wilderness of Riverside Park. He moved here from the woods and fishing of his country origins in Amherst, Massachusetts, a town whose population is just a few thousand people over the total number of enrolled students at Columbia University.

In Massachusetts, where his father worked as a professor at Amherst College for 40 years, when DeMott wasn’t playing soccer, or basketball, or tennis, or driving his dad’s car out into the woods to read Plato, he would listen to music: jazz and soul and the blues, Bob Dylan’s “Talkin’ New York.” Eventually, he says, the song got to him. He also knew that Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, two authors whom he admired, would hang out at the West End Bar near Broadway and 114th Street, and he liked the gym at Columbia, so he decided to head south for the city.

It was autumn of 1969 when DeMott, 18 years old at the time, first stepped onto campus as a Columbia student.

“I came down [to Columbia] with a concept of, ‘I’m going to read more Plato.’ I came down with a concept of, ‘I’m going to go to a good school, I am going to find great teachers,'” DeMott recalls. But, three semesters before DeMott arrived, the school that Columbia College Dean James Valentini touts as “the greatest university in the greatest city in the world” was swept up in a maelstrom of activist anger that shut down the campus for a week, caused the University president to resign, and forced the New York Police Department to assist the Department of Public Safety in enforcing the law by physically removing protesters on campus.

DeMott’s welcome to Columbia, therefore, was not characterized by balloons and smiling NSOP orientation leaders at the gate. Instead, political graffiti expressing the outrage of students against their university’s contributions to the Vietnam War and Columbia’s plans to build a segregated gym in Morningside Park burdened the entrance into the school.

In his suite on the ninth floor of Carman Hall, DeMott shared a room with Steve Cohen, part of the Columbia College class of 1973, who would be arrested later that year during a raid on Carman led by 20 plainclothes cops for “breaking down one of the doors of Low Library.”

In the middle of all this—the graffiti, the raid, the political demonstrations, and police beatings on campus, what DeMott calls a “whirlwind of ideas”—it wasn’t long before he too was inculcated into a culture of anti-Columbia activism, spending much of his free time in Carman smoking pot and engaging in political discussions to the sounds of Steve Miller and Led Zeppelin on the record player.

“I was just doing what was right,” he explains. “We shut down the University. There was no classes. … Sometimes, the professors just gave people a pass … [and] would hold their classes outside, not just ’cause it was a nice spring day, [but] because there was some shit goin’ on, some political action.”

By 1971, DeMott had received an injunction and was banned from going onto campus because of his participation in student a protest. Though he was no longer allowed onto school grounds, meaning that he was unable to attend any classes, he had not technically been expelled. Nevertheless, DeMott soon decided to quit Columbia. The campus politics were distracting him from Plato.

After leaving college, DeMott worked two jobs for a while, one at a bookstore and the other at the Manhattanville station of the U.S. Postal Service on 125th Street, where he would continue working for the next 30 years.

In 1978, seven years after dropping out, DeMott had a wife, Maria, and a son, Jamie, whom he named after James Brown. Maria was working for the University, and so DeMott took advantage of the opportunity to take free classes at Columbia until, eventually, he decided to work the late-night shifts at the post office and dedicate the daylight hours to full-time university study.

DeMott completed his bachelor’s in English at Columbia College in 1980. “Naturally, I didn’t go to my graduation,” he says, chuckling.

Long after the age of “gym crow” and the end of the Vietnam War, DeMott has continued to fight against Columbia. Spend just a short amount of time speaking with DeMott, and it won’t be long before he brings up his “10-year battle” against the University’s Manhattanville campus expansion or tells you about how “the presence of Columbia [is] so damningly elitist.”

Nowadays, DeMott speaks about the battle in past tense, although he says, “If we have a thinking and reflective mind, we are always in the middle of battles.”

Recently, DeMott has occupied himself with other activities: his short stories, his music, his songs, his poems, his paintings, taking care of his mother who passed away last spring, tending to his three cats (Twilly, Iris, and Homes), and warbling “Help me Jesus” to Shailaya.

This is the first personal profile of a man whom the media most often depicts shouting, not singing. His house, filled with old records and books like Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids and Games for Reading, reveals that there may be a person behind the political character. I wondered whether DeMott’s experience at Columbia had shaped anything other than his activism.

“I had a couple of professors who really encouraged my writing,” DeMott says. “That was helpful, and that gave me a sense of confidence.”

But DeMott’s identity as a Columbian, not as an anti-Columbian, is tenuous. He doesn’t consider himself a Columbia Lion. He finds the term “Columbian” too limiting, although he points out that he is also hesitant to label himself an activist. He is not proud of having gone to Columbia.

“I would be proud of it if everybody had a chance to go there,” he says. “I don’t worry about and never thought about being a part of the Columbia community. The whole idea scares me. … I certainly felt a sense of community while I was at Columbia. It just wasn’t Columbia University.” It was the student activist community.

DeMott’s relationship with the University is, and perhaps has always been, divided between loving his classes and hating his college. A poster of Bob Dylan, a man whose song had helped to bring him here, was up on the wall of the dorm room his first year at Columbia, where he would pin a political button on his chambray shirt before going outside to demonstrate. For DeMott, though, such a division is not a conflict nor is it a hypocrisy. He says that his relationship with the University is like a person’s relationship with a musician: Some songs are “the greatest thing in the world,” and some are “a piece of crap.”

“I can really point to Columbia University as an institution and really think that it reflects some of the worst things about culture and about civilization,” DeMott says. “At the same time, I can love the classes. I can love the intellectual experience that I had even fighting against the place.”

A few days prior to our interview, I hung out with DeMott for an hour at what he calls the 29th annual West Harlem Anti-Gentrification Street Fair, a low-key block party on Tiemann Place. There, I told him that WikiCU had named him “enemy of the state.” He laughed.

As the light dims in the comfortable apartment, I confess to him that I didn’t want to use WikiCU’s words to name this article. “Frenemy of the state” I thought would be more accurate.

“Frenemy of the state,” DeMott repeats. “I don’t quite buy that. I think enemy of the state is a closer truth, and I think it’s funny too, by the way, and I actually think it’s quite complimentary.”

At the end of our interview, DeMott is still sitting on the piano bench. He cradles his guitar like a soft kitten. He plays an original, “On The Shoreline.” I halfway expect to hear a lamentation of the loss of some of the old Manhattanville—after all, DeMott now lives in the shadow of the Columbia campus expansion he’s spent the past decade protesting. But I’ve assumed too soon.

“He came along one step at a time down the shoreline to love me. She came along in wind so strong down the shore line, down the shore line to love me,” he croons.

“Maybe this is the man behind the Manhattanville Tom DeMott,” I think to myself, and then I notice the large and colorful canvas partially obscured behind the bench.

“HARLEM IS NOT FOR SALE,” DeMott has painted on it in red, black, and green. I realize then that I’ve been looking at it all wrong: the Bernie Sanders sticker on the front door, the outsider art on the walls, the books (Junk Politics: The Trashing of the American Mind, which was written by his father Benjamin DeMott, is shelved alongside The Baroque Poem)— “A part of my everyday life is always resisting bullshit,” DeMott had told me.

There is no person behind the politics. Activism is behind Tom DeMott.